Submitted by Anna Davies on Mon, 23/04/2012 - 17:03

This month, we interviewed Dr Mark Holmes from the Department of Veterinary Medicine. Mark was recently interviewed on the Today programme about his involvement in a recent study of divergent strains of MRSA, published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

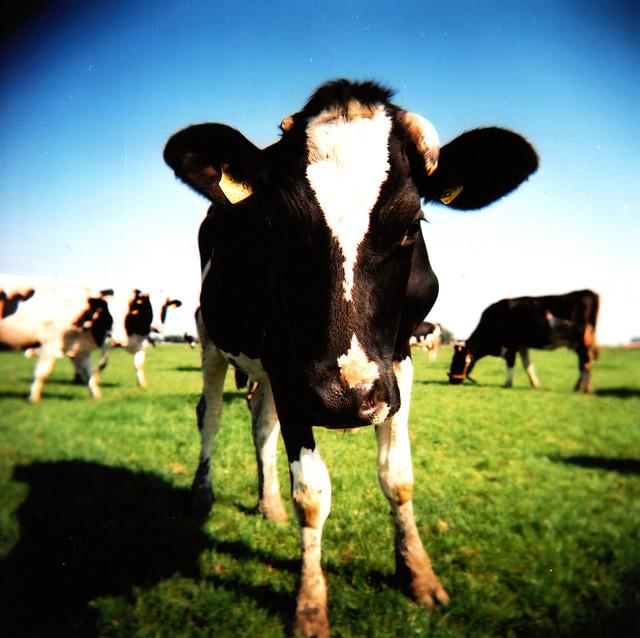

The study, which looked at mecA negative MRSA strains from dairy farms, identified a divergent mecA gene inside a mobile genetic element, which was only 70% homologous to S.aureus mecA, and undetectable using standard molecular methods.

The study, which looked at mecA negative MRSA strains from dairy farms, identified a divergent mecA gene inside a mobile genetic element, which was only 70% homologous to S.aureus mecA, and undetectable using standard molecular methods.

What led you to become interested in your area of research?

Although my background is in veterinary immunology, I developed an interest in epidemiology as a tool to investigate veterinary disease. I wanted to build a mathematical model of disease transmission, and make field observations that would verify the ability of the model to make predictions about future outbreaks. To build the model I needed to identify an endemic disease where it was also possible to track individual bacterial strains from one farm to another farm. Bovine mastitis was ideal, because the pathogens that cause it are fairly ubiquitous, but not completely ubiquitous, so it is possible to use strain typing to follow an infection from one farm to another. The movement of animals from one farm to another is an important risk factor and as there is now compulsory recording of farm animal movements maintained by the British Cattle Movement Service it was a convenient area to work. One of the risk factors associated with mastitis is antibiotic resistance, so when Laura [Garcia-Alvarez] collected a batch of strains she decided to test them. The Foot and Mouth Disease outbreak occurred in the middle of our collections, so because we were stuck in the lab, we used this as a way to occupy us. It was serendipitous that this led to the discovery of  the divergent mecA gene.

the divergent mecA gene.

The rest of my research is mainly clinically-oriented: clinical trials and epidemiological studies. Drug trials are performed in a setting designed to provide maximum control, so that even with farm animals, trials will have been performed in a research institute with individual housings etc. Just as with human drug trials there are a number of phases including clinical trials, it’s necessary to perform trials on active farms. Most veterinary drugs are developed as human drugs first, which, since lots of toxicity work has already been done, speeds up the whole process.

Over the next 20 years, what do you think are going to be challenges you are going to face-where do you think your research is going to take you?

I think that the challenge will be to turn research into a genuinely ‘one medicine’ scenario. At the moment veterinary and human medicine are separate, and although some veterinary medicine is researched as a model for human disease, there is very little comparative research that considers disease as a phenomenon that affects more than one thing. MRSA is a good example: humans can get S. aureus mastitis and although it’s not very nice it’s not the same disease as in cows. There is very little research is done on cow S. aureus/MRSA because it’s seen as a human pathogen, and yet now we’re beginning to see exactly the same organism being found in people and in cows, which means that we should be thinking about the epidemiology of disease control, not just in humans but animals as well. The more we research the comparative aspects of things like S. aureus, the better we’ll understand the situation. It used to be thought that there would be human strains, bovine strains and pig strains of S. aureus but it’s clearly not as simple as that, because we have found strains in pigs and people, and cows and people. Why are these ones breaking out? It could be that in the past there was no real restriction, just opportunity, i.e. cows only came across cow MRSA. The likelihood is that there is a gradient and that given sufficient opportunity any S. aureus will cause disease in another a species, but the majority live on that continuum. Some will jump easily, some won’t, and understanding what those factors are will be interesting. Another big excitement is the increasing ease of whole genome sequencing, because, with my epidemiologists hat on, understanding disease transmission as a result of very fine resolution phylogenetic work is going to revolutionise how we work, both as clinicians and researchers.

Who do you think has influenced you most in your career?

My first PhD supervisor, Neil Gorman (now Vice Chancellor at Nottingham Trent University), who taught me the importance of the application of scientific method. Most people learn what scientific method is either at high school or during their degree even if they don’t do it consciously. It’s when you start asking questions, and trying to solve problems, that you realise that rigorous application of scientific method is ultimately the only way to arrive at the truth, whether you are problem solving because your assay doesn’t work, or you are trying to work out what is a good research question. I think that far too many people forget about scientific method - every PhD student should be forced to take an exam in some scientific philosophy because although in a way it’s very simplistic and it doesn’t always reflect some of the problems in the real world, it’s when we forget that we’re scientists that things go wrong.

What is the most important lesson life has taught you?

That it’s much more important to include authors or acknowledgements than to not include someone. You have nothing to lose by adding an author, but I have regretted on more than one occasion missing somebody off who had materially helped with the research. No research is done in isolation –we ended up with 20 authors on the MRSA paper and every single one of them contributed to the work. It’s very sad when you get very narrowly defined research groups that just plough their own furrow, because whenever I’ve done something useful is when I’ve encountered someone outside my usual sphere.

I think good communication is also essential: I’ve had lots of problems due to lack of communication, but never a problem with over-communication. I might have irritated people by talking too much, but things often go wrong when people don’t talk to each other. If Cambridge Infectious Diseases promotes more communication that can only be a good thing and people should be encouraged to participate.